The Enchanted Basin

This is the Cairo Hospital for Dermatological and Reproductive Diseases. It’s a very nondescript building, but it commemorates one of the most magical tales of Historic Cairo: the Enchanted Basin, or al-Houd al-Marsoud.

We first hear of the basin from ibn Iyas, a historian of the Mamluk era writing in the 1400s.

Centuries earlier in the 900s, he tells us, before the city of Cairo was founded, there was a mysterious basin made of “dark stone and inscribed with the writing of birds.” It magically floated back and forth across the Nile, and people used it as a ferry to cross the river.

The wazir at the time, Kafour al-Ikhshidi, an Ethiopian slave who had effectively become Egypt’s ruler, wanted to understand its secrets, so he ordered it removed from the river for examination. As soon as it touched land, it lost all its powers.

The basin then disappears from history until 1615, when an Italian nobleman, Pietro della Valle, came to Cairo.

Drawing of the Lovers Fountain by Luigi Meyer (1755-1803)

Back home in Italy, della Valle had had a disastrous love affair and was considering suicide, until a friend suggested he take a trip to the East to distract himself with adventure. Cairo was one of his first stops. He writes that he visited the basin here, on Saliba Street at the foot of the Kabsh Plateau by the ruins of an old palace.

Della Valle calls it the Lovers’ Fountain. Set in a marble niche, it was large, made of dark stone, inscribed with hieroglyphs and what he recognized as an image of Anubis. Residents told him it had been left by the Ancient Sages and had magical powers. Whoever suffered from a romance, they said, could drink from it and “be relieved of the torments of Love.”

Despite his painful affair, della Valle declined to try it out. “I do not want Love to pass me by,” he declared. Also, he noted, the water was murky and livestock drank from it.

The Lovers’ Fountain was visited by multiple travelers over the next two centuries. The German-Italian artist Luigi Meyer drew the niche and palaces surrounding it in the 1700s. At one point, it’s said the Ottoman governor wanted to build a fountain of his own, so he ordered the basin brought to him. The workmen came, and a crowd gathered to watch, believing there was treasure buried beneath it. The workmen pulled and pulled but couldn’t move it. It was magically fixed to its spot, some said; others said they managed to budge it slightly, but it instantly slid back in place on its own.

When the British traveler Edward Lane visited Cairo, locals told him that Jinn held a market at the foot of the Basin every midnight for the first 10 nights of the Islamic month of Muharram. If a passer-by happened to buy dates or cakes or fruit from them, he would later find his purchase transformed into gold.

The Sarcophagus of Hapmen. Source: The British Museum

Then the French invaded Egypt in 1798.

The French Savants documenting Egyptian antiquities came across the Enchanted Basin. They described it as “a beautiful, black granite sarcophagus … about which” — they added with a sniff —”the locals tell many absurd stories.”

The French planned to ship it back home with a trove of other antiquities. But the looters were looted. When the French in Egypt surrendered to the British, they were forced to hand over everything they had collected. The Basin and other booty were instead taken to London.

The Basin now sits in the British Museum, identified as the sarcophagus of Hapmen, probably a nobleman of the 26th Dynasty around 600 BC. It closely matches all its visitors’ descriptions of a black, heavy stone, completely covered in hieroglyphics — “the writings of birds” — with Anubis prominently displayed in several places.

Though the Basin was gone, its power in curing the torments of love must have been ingrained in the place where it once stood, because the British set up a venereal disease hospital on this spot in the early 1900s. Sort of like the way you sometimes find a church or a mosque has been built on top of a former pagan temple, drawing from the same sacredness.

Under British colonial rule, it was here that registered prostitutes came for their required annual medical exams. When they emerged with a clean bill of health, they celebrated, singing, “Salma ya Salama, ruhna wa geina bil-salama” _ “Healthy and safe, we came and went in health.”

The great Egyptian composer Sayed Darwish and lyricist Kheiry Bishara heard the tune, and in 1919 they repurposed it, using it in their song about an exile’s nostalgia for his homeland, according to the Egyptian journalist Moamen al-Mohammedi in his book “Kull al-Awatif,” which gives the histories of 100 well-known Arabic songs.

The song was popular in Egypt, and then became a huge international hit in the 1970s, when the Italian-Egyptian-French diva Dalida made it her own.

And so a wandering, discursive thread connects a 2,600-year-old Pharaonic official to one of the most popular Arabic songs of the modern era and its joyous, crowd-rousing refrain.

The current, state-run dermatological hospital here still goes by the nickname of al-Houd al-Marsoud. And it has inherited the location’s magical reputation.

A friend of mine tells me that when her newborn son was suffering from a skin rash in the Cairo summer heat, her aunts told her to go to al-Houd al-Marsoud. The aunts were born and raised in this district, Hilmiyya, and their mother had always told them that not only does the hospital boast some of Egypt’s best dermatologists, the location itself has healing powers.

Meanwhile (and I know you were worried about this), Pietro della Valle did find love again. Passionate, overwhelming, and ultimately rather macabre love.

After leaving Cairo, he travelled around Syria. To pass the time wandering the countryside of Aleppo, one of his companions regaled him with descriptions of an extraordinary beauty he had met in Baghdad: Sitti Maani Gioreida, the daughter of a Chaldean Christian family.

Just from hearing these stories, “my impatient heart was totally consumed,” della Valle writes. He was filled with “a passionate desire to meet face to face with a person of such perfection.”

He headed to Baghdad and secured an introduction to the family. During dinner, the 18-year-old Maani hands him an apple, and he is enraptured. He admires her shapely form and grace in speaking, the arch of her eyebrows and her kohl-lined eyelids that appear as “majestic shadows” over her glowing eyes.

After closing off his heart to love for so long, “I was now reduced to an excessive, amorous furor,” he writes.

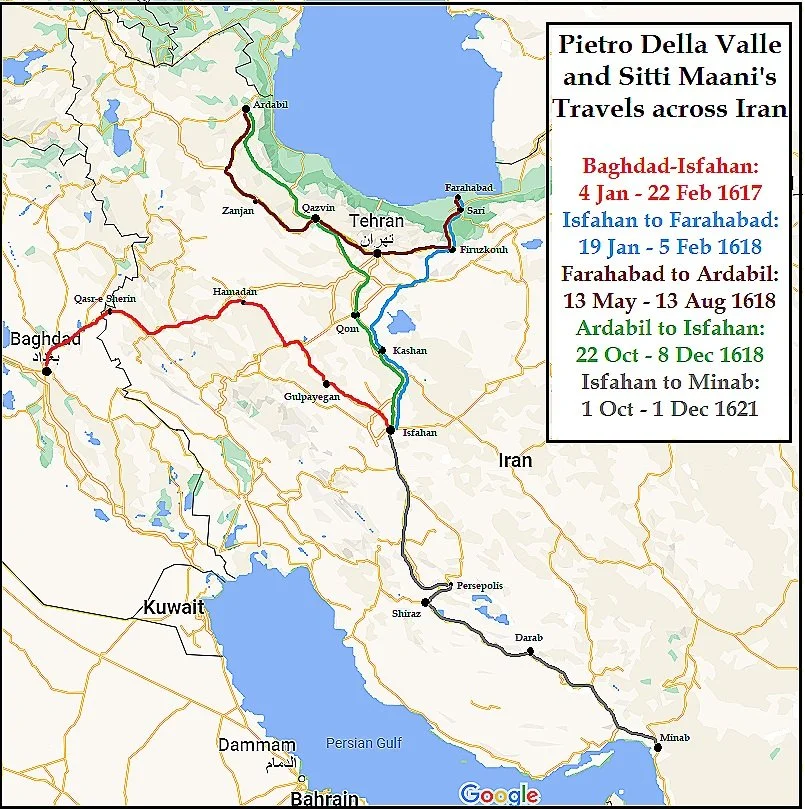

By December 1616, they were married. After a time in Baghdad, they set off together for more travels in Persia. Della Valle recounts every detail of his voyages in long letters to a friend back in Italy, which were compiled into an 8-volume book titled Viaggi di Pietro Della Valle il pellegrino.

In them, he describes Maani as his perfect companion:

“She fears neither heat nor cold … She prefers staying under the tents in the field to a place indoors, uninterested in sleeping luxuriously in delicate beds ... She has all the necessary qualities, whether for travel or for war. She rides horses like a true cavalier, with one leg on either side, armed like an Amazon, galloping always beside me.”

Maani was daring, curious and determined.

During a stay in the Persian city of Kashan, while della Valle was off touring the library of a Jewish doctor from Safed who offered to teach him the secrets of mercury, Maani wanted to explore the local bazaar. Since ladies of quality were not supposed to go out in the city streets, she disguised herself as a servant. As she and one of her ladies strolled through the market, a group of drunks harassed her, for she had completely forgotten “she was in the garb of those who might be exposed to such indignities,” as della Valle puts it. Her guards, following discretely behind the whole time, intervened. An argument ensued, swords were drawn, and one of the harassers fell to the ground, his limbs hacked half off, and bled to death.

Told of the altercation later, della Valle admired his wife’s “intrepidness at the sight of this bloody melee.” Afterwards, he writes proudly, she calmly “continued her way without shock or further disturbance.”

Together, they crisscrossed Persia, through snow-laden mountains in Kurdistan to the shores of the Caspian Sea in Mozandaran, past plains of salt and across deserts to view the ruins of Persepolis and the palaces of Shiraz. Maani rode her horse Dervish at della Valle’s side, or at times retired to her litter, big enough for four people, swathed in satin and silk and carried by two camels.

They stayed in palaces of local khans, in fine houses of merchants and rural caravanserais, in the ruins of forts and outside under stars. During stops in the countryside, she walked into tiny villages, eager to see how they lived, and had meals with local shepherd women. She mingled with nobles and generals and dined with the wives of local lords. She didn’t hesitate to accompany della Valle as he joined the Safavid ruler Shah Abbas in a military campaign to battle the invading Turks at Ardabil.

Della Valle paints a vivid picture of Maani. But she remains at a remove from us, because in his passion for her, he doesn’t just want to depict her, he wants to shape what she is. He’s driven to simultaneously exoticize her as a creature of the East and re-create her as a European.

In one letter, he veers into an allegorical fantasy that transplants his voyages onto a Baroque landscape of Classical Mythology. There, he is on a quest to find and triumph over Aurora, the Roman goddess of the Dawn and a symbol of the East.

He describes enduring the dangers of unknown roads and battling cruel barbarian giants until finally he reaches Aurora’s palace. There, he is dazzled by its decorations of rubies, ebony, ivory and sandalwood. He presents himself to the goddess and declares his love for her.

Aurora rejects him. But she does admire his boldness. So she leads him into a secret garden where “a thousand and a thousand Nymphs frolicked” among cedars and palm trees and flowing streams, the air filled with the scents of roses, spikenard, cinnamon and peppermint.

Aurora picks out one nymph and gives her to him. “Out of all the Nymphs I cherish,” she tells him, “the Heavens have made this one your destiny.”

This was Maani Gioerida.

“The more I possess her,” della Valle writes, “the more I desire to possess her.”

“Aurora Taking Leave of Tithonus,” Francesco Solemena, 1704, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

It ends in tragedy.

In 1621, della Valle and Maani, now pregnant with their first child, find themselves stranded in Minab, a backwater town by the Straits of Hormuz, waiting for a British trading ship to take them on their next stage of travels. Afflicted by the town’s “bad air,” Maani falls ill. She suffers a miscarriage, then after a week of worsening fever dies at the age of 23.

Della Valle is crippled by despair. Once so driven to conquer the East, he became convinced that his wife’s death was God’s punishment “to defeat my pride.”

“Pietro della Valle has ceased to be,” he writes to his friend in Italy. “All that is remains of him is a naked, unhappy shadow, left on this Earth as a punishment by God, not to live but to pay for the enormous mistakes of his life.”

He couldn’t bear the thought of being separated from Maani or of burying her “in the land of the Infidels.” So he decided to bring her to Italy. A group of women embalmed Maani in a “large quantity of camphor” and, eager to prove the quality of their work, displayed to della Valle her preserved heart on a saucer before reinserting it into her body.

He placed her in a coffin of mango wood. Because he can’t help but document every bit of exotica in his travels, he interrupts his grief to digress for several paragraphs about mangoes. He notes that the mango is unknown in Italy, he describes the tree and its fruit, and he adds: “I have never eaten one, but I have eaten them pickled, like olives …. In this way, they are excellent.”

He then proceeded to carry Maani with him in her mango-wood coffin during his continued travels.

FOR THE NEXT FOUR YEARS.

He crossed the Arabian Sea and toured Moghul India. He hid the coffin among furnishings and bales of cotton to get it past border authorities or ship captains unwilling to transport a body. On his return journey home, crossing the deserts from Basra to Aleppo, his caravan was stopped by Bedouins. They rummaged roughly through their belongings, looking for valuables. But when they found Maani’s coffin, della Valle says, they left him alone because they were so moved by “my resolution to bring her back to my homeland for her last rites and to place her in the sepulchre of my ancestors.”

Which he finally did.

Arriving in Rome in 1626, he had Maani placed in his family vault at the church of Santa Maria in Aracoeli on the Capitoline Hill. He married Mariuccia, a Georgian orphan whom his wife had adopted in Isfahan and who had accompanied him throughout his travels. She had 14 children with him. When he died in 1652, della Valle joined Maani in the family vault.

Santa Maria in Aracoeli, Capitoline Hill, Rome

Let’s end by going back to that moment when della Valle puts her in that vault.

Just before he does so, he opens the coffin for the first time after so many years of travelling with it. He examines the body, notes its good condition. But he balks at unwrapping her face. Perhaps the thought of seeing his love’s face was too inconceivable, too horrible.

It’s understandable, but it also feels like a final reluctance by della Valle to gaze on the reality of Sitti Maani Gioerida. We too can’t look upon her reality. We don’t know what she felt about this European stranger who swooped into her life. We know nothing of her impressions of their travels, we don’t know how she would have felt to be buried so far from her homeland.

Anything we know about her comes to us through him, colored by his passion for her and by his own considerable ego. The stronger his love for her burns, the more the light is meant to illuminate him. We want to see her somewhere there, but instead we only see the question: Does he… do we? love for the benefit of our beloved or just for the benefit of ourselves?

As della Valle wrote in a letter, while he and Maani crisscrossed Persia together:

“My Muses work only for Gioerida. Kingdoms, seas, rivers, forests and mountains all know Gioerida from my writings. This will be the means by which the centuries to come will admire Gioerida.”