The Palace of Fatima al-Khasbakiyya

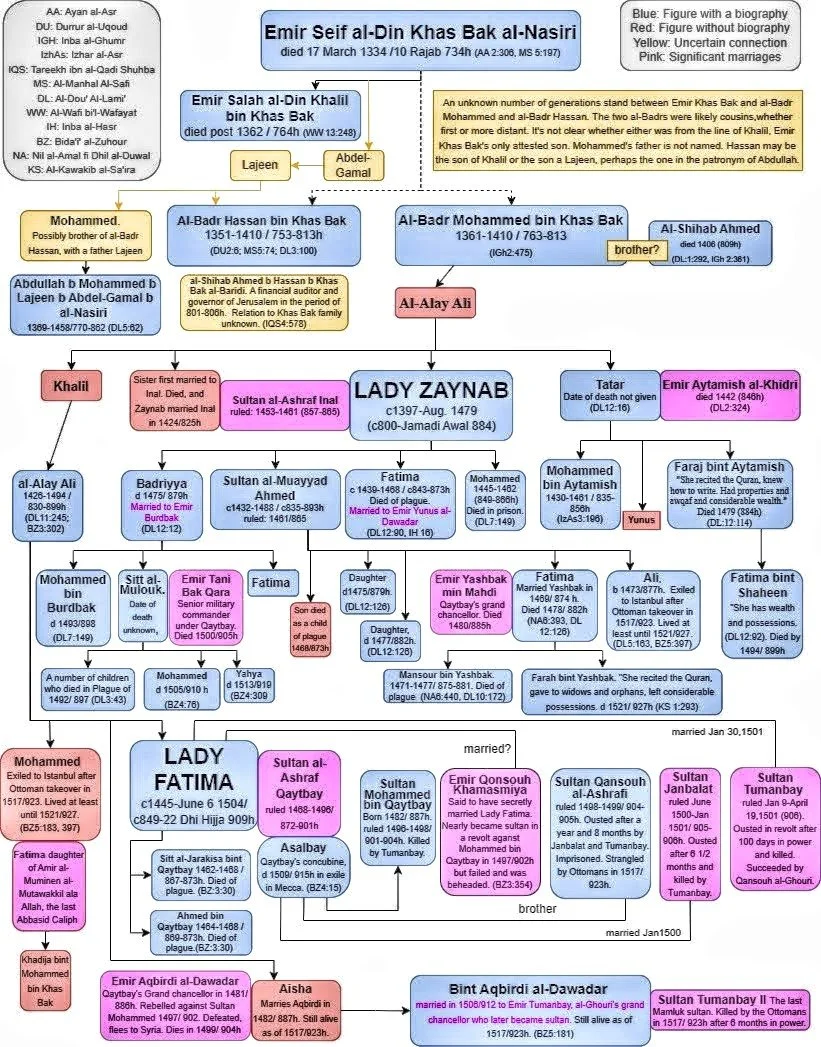

A single great family sprawls across the last 60 years of the Mamluk Sultanate in the 15th Century. It’s largely hidden from view because its most important members were women, but for multiple generations it was intertwined with power and wealth.

This was the bin Khas Bak family, or the Khasbakiyya.

The family is centered on two women, both of them wives of sultans: Lady Zaynab, the wife of Sultan Inal, and her great-niece Lady Fatima, the wife of the great Sultan Qaytbay. (1)

Both exercised political authority unheard of for Mamluk women. They were both not just wealthy, they were active businesswomen, buying up properties and building estates. Their money and political prominence filtered down through the family to their daughters, granddaughters and nieces. Look closely at any of the most powerful Mamluk emirs of that time and there’s a good chance you’ll find him married to a bin Khas Bak woman. The husband of Lady Fatima’s sister nearly became sultan, and Lady Fatima’s niece was the wife of the last sultan of the Mamluk Era.

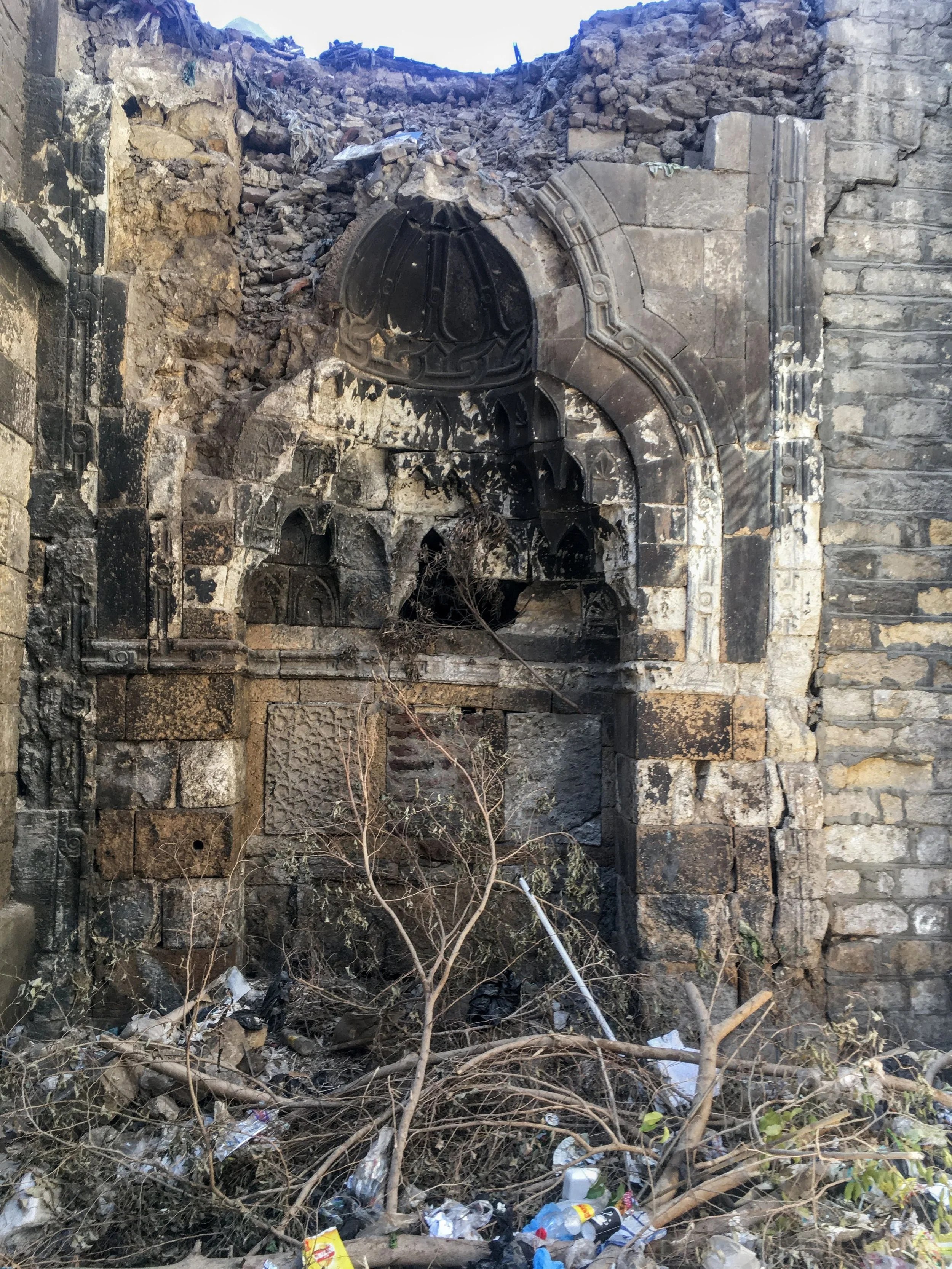

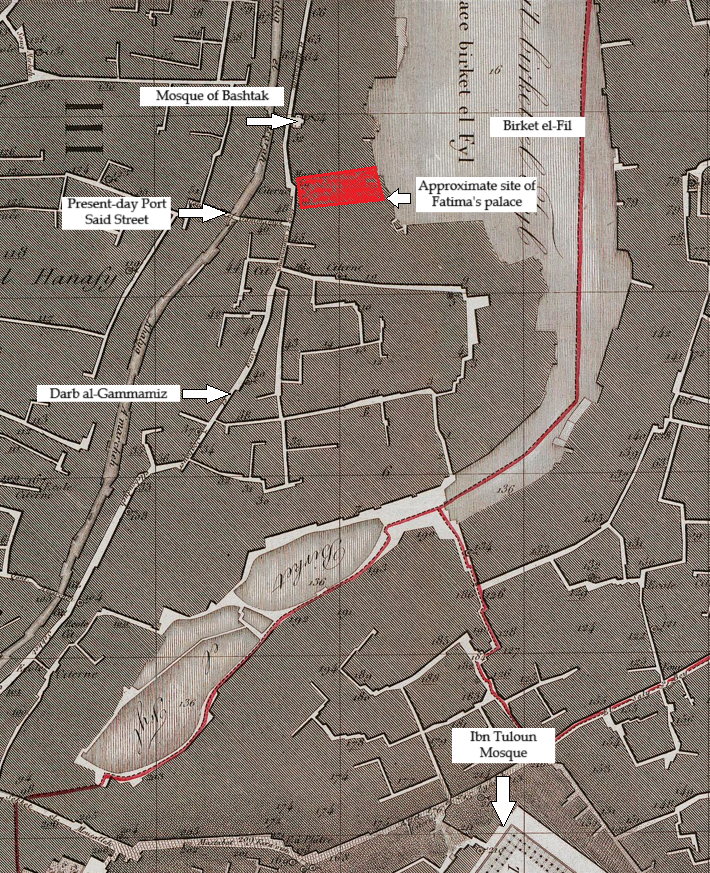

This location where we’re standing, the Old Hilmiyya Middle School for Boys, is where Lady Fatima’s palace stood in the late 1400s. (2) At this intersection, the narrow north-south street is one of the last surviving sections of a 1,000-year-old lane, Darb al-Jamameez, or Sycamore Path. No doubt the palace’s front entrance opened onto it. (To your left, on the north side you see the minaret of the 14th Century Mosque of Bashtak. Follow Darb al-Jamameez south and you enter a pocket of streets whose layout hasn’t changed since Mamluk times.)

The larger cross street, Ahmed Omar Street, was laid down in the 1950s. It paved over what had been gardens surrounding the Khediviyya Secondary School, Egypt’s first modern high school, and the Kitabkhana, the first state archives, both installed in this location during the modernization drive of 19th century. (3) That was the dawn of Egypt’s Belle Epoque, which was also the heyday of this district, Hilmiyya. Today, the street throngs with kids. They charge out of the gates of the many schools nearby bearing names from that time — the Khediviyya, the Saint Vincent de Paul, the Refaa al-Tahtawi — and crowd the kiosks for sodas or congeal shrieking and laughing into cliques between and on top of the parked cars. Nearby, men haul couches and chairs and dining room tables. This is a favorite place for moving company workers to park their big trucks while they load them with furniture, because the street is wide but little trafficked; its era has passed, and it no longer leads anywhere important.

Follow the wall of the school until you reach the gate of the neighboring girls’ high school. It is approximately here that, 500 years ago, Lady Fatima’s palace met the banks of Birket el-Fil Lake. The lake, which once took up a large part of what is now Hilmiyya, was lined by grand mansions of the elite during the Mamluk and Ottoman periods. Overlooking the lake, Fatima’s palace probably extended over the entire lot of the present-day school, with gardens and an attached hammam, or bathhouse.

But we’ll come back to Lady Fatima later. Let’s start with the real grand dame of the family, the one who set it on its track of influence: Lady Zaynab bint Alaa al-Din Ali ibn Badr al-Din Mohammed bin Khas Bak, most often known as Lady Zaynab bint Khas Bak.

LADY ZAYNAB

Zaynab was born sometime before 1397 to a family hovering in the lower fringes of the Mamluk Era elite. They had a respectable pedigree, able to trace their line on the men’s side to the eponymous Emir Khas Bak — a favorite Mamluk of Sultan al-Nasir Mohammed — and, on the women’s side, to Sultan Baybars, the first great Mamluk sultan in the mid-1200s (4). The bani Khas Bak men were Islamic scholars, but not prominent ones, and they held no posts in the court, the bureaucracy or the mosques. The family was not particularly wealthy.

But Zaynab’s climb to power would transform the family. It was one of her sisters who first married a low-level Mamluk emir named Inal al-Alaa’i, but the sister died soon after, and Zaynab was given in marriage to her widower. Over the next two decades, Inal rose through the ranks of the Mamluk leadership and eventually became commander of the military under Sultan Jaqmaq. After Jaqmaq’s death, Inal toppled Jaqmaq’s son and seized the throne for himself in 1453 to become sultan.

Now the sultan’s wife, Zaynab moved into the Hall of Pillars, the center of the harem in the Citadel, and took on the title of “Khawand al-Kubra,” or Great Lady.

From the start, she was clearly a powerhouse, and it’s said her husband and top officials bent to her will. It’s a sign of how formidable Zaynab was (or, if we are charitable, of how much in love with her he was) that Inal never took a second wife alongside her. In fact, he never even had a concubine.

All the chroniclers of the time marvel at her authority.

“She was unique among great ladies for her influence and the sultan’s obedience of her orders,” al-Sakhawi writes. “She came to manage the affairs of state, determining appointments for positions,” ibn Iyas says. Ibn Taghribirdi adds, “The sultan never contradicted her commands.”

Or as the religious scholar Taqieddin Ibrahim al-Biqai put it: “She was the sultan, not Inal.”

Al-Biqai is our best source on how Lady Zaynab wielded her power. He was a groundbreaking religious scholar who used Christian and Jewish scriptures to help interpret the Quran, outraging many of his contemporaries. He served in Inal’s court, had close ties with many of its senior officials and knew the ranks of the religious scholars personally.

Fortunately for us, he was also a dishy, dishy gossip.

Prickly, censorious and convinced of his own moral superiority, al-Biqai flings dirt on everyone in his 3-volume personal history, “Izhar al-Asr li Asrar Ahl al-Asr,” or “Illuminating the Dusk on the Secrets of the Men of the Era.”

He depicts Lady Zaynab as a fount of corruption, a woman who meddles in state affairs to elevate her favorites and undermine her opponents in petty personal grudges. Al-Biqai’s accounts may be exaggerated and, aside from his just plain misogyny, he did have an agenda; Inal was considered a weak sultan, so it’s convenient to blame his failures on a domineering woman. But what stands out about his portrayal is that Lady Zaynab acts much like any sultan did, elevating and lowering underlings on the basis of money, friendship or loyalty.

Her crime was that she was a woman playing this game. And it turns out many women were doing so. As he enumerates examples of Zaynab’s supposed corruption, al-Biqai ends up showing us how women networked behind the scenes to influence court politics.

Take his account of the case of Abu’l-Fatah ibn Harmi, a wealthy merchant.

One day, one of ibn Harmi’s slaves riding his mule trampled an old man to death in the center of the city. The old man’s son, who was poor, asked ibn Harmi for compensation but was soundly rejected. So the son turned to the governor of Cairo, who arrested ibn Harmi and publicly humiliated him by putting him in chains.

But ibn Harmi’s wife and daughters took his case to Lady Zaynab. She immediately had the merchant freed.

The governor and all the other emirs were furious over the women’s interference. The governor complained to Sultan Inal that his prestige had been undermined. Inal was sympathetic and ordered ibn Harmi arrested again. But before his orders could be carried out, ibn Harmi’s wife once again appealed to Lady Zaynab.

The next day, it was the governor who was summoned before the sultan, who shouted at him and humiliated him in front of all the other emirs. The governor could do nothing but stand silently and take it.

Protected from on high, ibn Harmi “only became more arrogant,” boasting to all who would listen how his women had bested the governor.

Or there is the case of Badreddin al-Mahalli, the senior judge of Alexandria. He was notorious for his corruption. Al-Biqai writes with flourish that al-Mahalli brought together moral turpitude and physical hideousness, with “brutish features, a large mouth like a snake’s and big eyes, like those of rat bulging as it is strangled.”

A senior court official who clashed repeatedly with al-Mahalli over the proceeds from Alexandria’s port was determined to get rid of him. But the judge was unassailable, protected by Lady Zaynab and her son Ahmed because of the payments he regularly funneled to them.

So the court official sent his own womenfolk to work on cajoling Zaynab. Once they succeeded in turning her against al-Mahalli, all it took was one word from her to her husband and the judge was removed. Zaynab even overruled the opposition of her son, who still supported al-Mahalli.

Lady Zaynab was the center of gravity in Inal’s court. The three most powerful men in her husband’s inner circle answered to her as much as to the sultan.

First was her son Ahmed, who was in his 20s during his father’s rule and was being groomed to succeed him on the throne.

Then came her two sons-in-law. Emir Burdbak, a Cypriot and one of Inal’s favorite personal mamluks, was married to Inal and Zaynab’s eldest daughter, Badriyya. Though he held the nominally unimpressive post of 2nd Deputy Chancellor, Burdbak was in reality the sultan’s closest associate.

The other was Emir Yunis, a senior emir who backed Inal in the revolt that brought him to power. Inal rewarded him by naming him Grand Chancellor and marrying him to his and Zaynab’s youngest daughter, Fatima.

Lady Zaynab also had her own entourage.

Among her favorites was Khadija bint Baysari, the wife of the highest religious official in the sultanate, Chief Judge Alameddin al-Bulqini.

Chroniclers of the time say it was Khadija’s ties to Lady Zaynab that ensured her husband kept his position throughout Sultan Inal’s eight-year reign, despite the fact that — at least according to al-Biqai — Alameddin shamelessly took bribes and changed his rulings for whoever paid him.

On one occasion, Alameddin was caught helping a claimant use false witnesses to swindle an heir out of a piece of land. What’s striking is that not only did the sultan summon Alameddin and reprimand him, Lady Zaynab also brought in Khadija and berated her as well. Clearly, both women were active agents in their husband’s affairs (and clearly Khadija was in on her husband’s scam.) Still, Alameddin remained in his post and Khadija in Zaynab’s good favors. Linked to the most powerful woman in the land, Khadija ensured the rise of her son by an earlier marriage, Badreddin Abu Bakr ibn Muzhir, who eventually became one of the most important and wealthy officials in the court bureaucracy.

Lady Zaynab also protected her sister Tatar’s wayward son, Mohammed. The young Mohammed had surrendered himself to drinking, debauchery, song and the other worldly pleasures. “Rarely was anyone so bold in openly committing sin,” al-Biqai writes. But no one dared complain of him because of his aunt.

Once, he went too far. Mohammed abducted a beautiful slave boy belonging to an emir named Sunqur. The furious Sunqur, who was in love with the boy, stormed into Mohammed’s mansion, caught them together and nearly beat Mohammed to death. The sultan was furious at his wife’s nephew for the scandal but, mollified by Lady Zaynab, he forgave Mohammed and welcomed him back into court.

(Mohammed later repented of his ways and dedicated himself to religion, studying with some of the top sheikhs of his time. So his soul was in proper repair, al-Biqai assures us, when he died suddenly at the age of 30, keeling over after returning from a ride in the countryside with his cousin Ahmed and their friends.)

Along with her favorites, Lady Zaynab also had a nemesis: Zaynab bint Jaribash Qashoq.

Bint Jaribash, as we’ll call her, was a wife of Inal’s predecessor, Sultan Jaqmaq. She was young, only about 12 when Jaqmaq married her in 1438, just after he ascended to the throne. She could boast a fine lineage; her father Jaribash was a prominent emir, and more importantly her mother, known as Fatima Umm Khawand, was the great-niece of the great Sultan Barqouq. This Fatima was a model of public piety, studied Hadith and Quranic interpretation, could recite the Quran and spent her wealth in charity for the poor. A zawiya, or small mosque, that she built near Bab el-Shaariyah still stands, or at least part of the facade does.

The Zawiya of Fatima Umm Khawand, on al-Shaarani Street near Bab al-Shaariyyah. In 1887, the Comite dismissed it as having no historic or artistic importance. By that time the interior was already gone, leaving just a facade. Then a decade later, the Comite took another look, its interest sparked by its portal, which does boast a lovely spiral tendril design on its lintel stone. They cleaned up the portal and found an inscription identifying it as, in fact, a madrasa not a zawiya, founded by Fatima Umm Khawand. They were impressed enough to put it on the registry of official monuments in 1899, which was what has ensured its survival until today. Barely. There’s no indication the Comite ever did any renovation on it. At some point later, a school was built inside it.

Sultan Jaqmaq cherished bint Jaribash. They had a son, but the boy died as an infant. When Jaqmaq divorced his senior wife in 1448 (reportedly because he suspected she had poisoned his favorite concubine), bint Jaribash was elevated to senior wife. The 22-year-old was now the Great Lady of the Hall of Pillars.

Al-Biqai purports that bint Jaribash enjoyed numerous affairs, most famously with Shaheen Ghazali, a handsome Greek eunuch who served as one of the sultan’s cupbearers. This Shaheen was only partially castrated and whatever remained of his genitals was impressive enough, al-Biqai tells us, that bint Jaribash’s “desperation for it grew excessive.” She invited literati to come and write poems about his endowment.

Unfortunately, the poems leaked, and soon everyone in Cairo was singing songs about Shaheen’s prodigious partial penis.

Anyway — bint Jaribash relished tormenting our Zaynab. Like the wives of other top emirs, Zaynab had to frequent the harem in the Citadel, whether to attend events like weddings or just to sit in the entourage of the Great Lady. Whenever she did, bint Jaribash found ways to humiliate her. Al-Biqai doesn’t say why. Perhaps Zaynab had insulted her in some way. Or perhaps bint Jaribash just enjoyed the feeling of power over this woman 30 years her senior, wife of her husband’s top military commander.

But once Sultan Inal came to the throne, bint Jaribash was without protection.

The new Great Lady of the Hall, Lady Zaynab inflicted on her all the same slights she had once suffered. When Zaynab went on hajj, for example, bin Jaribash trudged behind the caravan on a donkey, while Zaynab, Zaynab’s daughters and the other women of court rode in the cushioned comfort of their litters.

More brutal was Lady Zaynab’s treatment of bint Jaribash’s new husband, Sharafeddin al-Ansari.

Al-Ansari was a merchant from the Delta province of Menoufiya who had maneuvered his way into Sultan Jaqmaq’s court and came to hold several high financial positions, making him a wealthy man. He and bint Jaribash were passionately in love, al-Biqai says. They married immediately after Jaqmaq’s death but initially kept it a secret, since al-Ansari was not of high enough station for a sultan’s widow. For nights with his wife, al-Ansari disguised himself as a common boatsman and rowed across the Birket el-Fil Lake to slip into bint Jaribash’s mansion, located very close to where we’re standing now. (5) Finally, in October 1458, Sultan Inal made al-Ansari supervisor of the army’s finances and gave his consent to the marriage, which could then come into the open.

The union only “brought ill upon them both,” the chroniclers say.

After only six months in his post, a furious Sultan Inal accused al-Ansari of embezzling funds and had him imprisoned.

Al-Biqai claims this was the doing of Lady Zaynab, who had swayed her husband against al-Ansari to spite bint Jaribash. Zaynab was ruthless. When her son-in-law Grand Chancellor Yunis tried to intercede on al-Ansari’s behalf, Zaynab ordered him to shut up. She urged Inal to have al-Ansari tortured to reveal where his money was hidden — but her other son-in-law, Emir Burdbak, secretly defied her and convinced the sultan to show mercy. Al-Ansari was eventually released, but only after much of his and bint Jaribash’s fortune had been stripped away.

Not long after, bint Jaribash died in the horrific plague outbreak of 1460, during which thousands dropped dead in Cairo every day for weeks.

Al-Ansari was heartbroken. Compounding his misery, his wife’s mother was convinced al-Ansari was cursed and had brought about her death. Bint Jaribash was buried in the grand mausoleum of her great-great-uncle Sultan Barqouq on Bein al-Qasrein, Cairo’s most prestigious street. Shunned by her relatives sitting in the main hall, al-Ansari could only watch his beloved’s entombment from a distant corner, out of sight and weeping.

Still, even al-Biqai can’t blame Lady Zaynab for the plague.

For all of al-Biqai’s demonizing of her, Lady Zaynab seems to have been enormously popular with the public.

In the spring of 1455, she fell ill and was taken from the Citadel to a palace in Boulaq to recuperate by the Nile. Her son and daughters went to care for her, and the high officials of the court, top emirs and judges all made pilgrimage to her door to ensure they were seen wishing her a swift recovery.

When she felt well enough to go to the bathhouse at the palace, celebrations erupted. The public crowded to the palace and lined the banks of the Nile to cheer as fireworks exploded and bands of tabla drums and trumpets played. The merriment went on into the night, and the crowds of men and women mingled so openly that the historian ibn Taghribirdi was scandalized, saying: “All sorts of corrupt and dissolute things happened after nightfall.”

Once she was well, Zaynab returned to the Citadel in a grand procession up Saliba Street, which was lit up with candles and lanterns. Her son and sons-in-law escorted her, followed by a parade of servants, eunuchs, women of the court and wives of the emirs.

Lady Zaynab’s popularity was presumably due to her wealth and funding of charity works. She founded a ribat, or home for widowed women, a fragment of which still stands today in the old city of al-Qahira. Before going on hajj in 1457, she funded the building of the Utayfiya Madrasa in Mecca, adjacent to the Grand Mosque housing the Kaaba.

Sadly, all that remains of Lady Zaynab’s ribat, located in the old city of al-Qahira near Bab el-Shaariyah

Photo of the same portal taken in 1916-1921 by Sir K.A.C Cresswell ©Victoria and Albert Museum, London

She also pushed her notoriously stingy son Ahmed to give of his own wealth to build up his public standing as he maneuvered to succeed his aging father as sultan.

And that is what happened when Sultan Inal, in his 80s, died in his bed in February 1461. Zaynab’s son ascended the throne, becoming Sultan al-Muayyad Ahmed. After only about four months, however, the other Mamluk factions rose against him and toppled him. Ahmed was led out of the Citadel in chains and taken to Alexandria Prison, while his father’s former commander of the military, Khoshqadam, was made sultan.

Here begins a long period of suffering for Lady Zaynab and her family.

Sultan Khoshqadam immediately targeted her wealth, accusing her of holding money that rightfully belonged to the treasury. The man he appointed to extract it from her was none other than Sharafeddin al-Ansari, the nemesis’ husband whom she had tormented. Marching into her home, al-Ansari spewed a torrent of insults and threatened that she would be jailed, and beaten if she didn’t pay.

Zaynab’s trials transformed her image. From the imperious, unquestionable mistress of the harem, she now becomes the model of a noble mother, enduring humiliation to support her son.

Her only wish was to go to Alexandria Prison to be by Ahmed’s side, but Sultan Khoshqadam would never allow this until she paid what he demanded. Zaynab was reduced to going around to the top emirs asking for help. None would lift a hand for her. She went to Khoshqadam’s Grand Chancellor and lowered herself to begging; the woman who had once been the most powerful figure in the sultanate took the dirty ends of her robes that had been dragging on the ground and covered her head with them in a sign of humility.

Al-Biqai relishes her abasement. “She deserved this,” he writes. Not just because she meddled in power, he adds, but also because she rarely prayed. In fact, he contends, the entire “Bani Khas Bak family were a house known for their lack of prayer.”

Eventually, she paid 50,000 dinars. Then the sultan demanded another round of money from her. After paying a second time, she was granted permission and left on a boat up the Nile to Alexandria in September 1461.

She would stay with her son in prison for the next six years. The family suffered a series of tragedies. Zaynab’s youngest child, Mohammed, who was imprisoned with his brother, quickly died of illness in 1462, aged only 17. Zaynab’s daughter Fatima came to Alexandria to attend the circumcision of a son of Ahmed, but she was struck with the plague and died _ as did Ahmed’s son. Three of Ahmed’s young daughters died over the following years.

The reprieve came in 1467, when Sultan Khoshqadam’s successor freed Ahmed from prison and allowed him to live in Alexandria. Their fortunes improved even more the following year when Sultan Qaytbay — the husband of Zaynab’s great-niece Fatima — came to power. He loosened restrictions further, even allowing Ahmed to visit Cairo. Still enormously wealthy, Zaynab retuned to Cairo to live, and it’s said Qaytbay respected her so much that he would stand whenever she entered the room.

In August 1479, Zaynab was on her deathbed, and Qaytbay granted her wish and allowed Ahmed to come to Cairo to see her one last time. She died at more than 80 years old, outliving all her children except Ahmed as well as many of her grandchildren.

A family tree of the Khasbakiyya over a stretch of 180 years. For further details about the family, click on the tree.

LADY FATIMA

Fatima was born sometime before 1445, the granddaughter of Lady Zaynab’s brother Khalil (of whom nothing is known.)

Qaytbay had been a simple Mamluk soldier working in the sultan’s secretarial office when Inal in 1459 elevated him to an emir of 10, the lowest rank of emir but the start of the military command track. Most likely, Qaytbay and Fatima married soon after that promotion, when she was in her teens and he in his mid-40s.

Qaytbay rose to the top with a swiftness rarely seen. Within nine years, he was “atabak,” or top commander of the military. In 1468, bloody factional chaos saw two sultans rise to the throne and then be toppled within the course of four months. Qaytbay then stepped in and took power. His marriage to Fatima helped win him the sultanate; the mamluks of Inal rallied to his side because he was their master’s in-law. Qaytbay went on to rule for nearly 30 years, the longest reign the sultanate had seen for more than a century. A far more powerful and dynamic sultan than Zaynab’s husband Inal, he reined in the rowdy Mamluk factions, restored the military to fighting prowess and launched a massive campaign of monumental building.

Throughout his rule, Fatima was the undisputed Grand Lady of the Hall of Pillars, the only wife Qaytbay ever took. “She was among the most famous of the Grand Ladies, renowned for her vast wealth,” the main historian of the time, ibn Iyas, writes. “She showed a might and majesty that no other grand lady had.”

Unfortunately, because ibn Iyas tends to say very little about women in his history in general, we’re sorely missing a gossip like al-Biqai to spill for us on how Lady Fatima exercised her influence. We can imagine she did so much like her great-aunt had. Certainly her father, Alaa al-Deen Ali, was a savvy peddler of influence in Qaytbay’s court. He pops up often to use his good offices and connection to the sultan to secure a position for a friend or help restore an ally who had fallen from favor.

Fatima and Qaytbay had two children, a daughter Sitt al-Jarakisa (“Lady of the Circassians”) and a son, Ahmed. Both died as young children in the plague of 1468, just after Qaytbay came to the throne. The tragic deaths robbed Fatima of her status as the mother of Qaytbay’s heir. Though she was only in her 20s at the time, Fatima never had another child.

Yet Qaytbay never took another wife. In fact, it looks like he didn’t take a concubine for another decade: There’s no word of Qaytbay fathering any more children until a daughter born sometime around 1478 to an unidentified enslaved woman. (6)

It was startling enough that Inal never had another wife other than Lady Zaynab, or even a concubine. But they had two sons and two daughters, all of whom outlived their father. In a way, Lady Fatima and Sultan Qaytbay’s case is even more remarkable. We can’t know why Fatima had no further children, but we can assume Qaytbay wanted a male heir; yet he seems to have balked at turning to another woman for a son for years, until he was in his 60s (and Fatima in her late 30s).

Perhaps he held off out of respect for the status of the Khas Baks. Or perhaps there was real devotion in Fatima and Qaytbay’s marriage. () A possible hint of actual affection between them does peek out from ibn Iyas’ accounts: Fatima repeatedly organized celebrations for her husband. When Qaytbay returned from hajj in 1480, Fatima personally lay sheets of silk on the ground along his path into the Citadel and sprinkled flakes of gold on his head while her servants blew clouds of saffron into the air. She did the same later to celebrate when Qaytbay recovered from a horse-riding accident that had left his leg broken and raised fears over his life. I may be reading too much into it, but in the many accounts of celebrations for sultans for all sorts of occasions, I can’t think of a single time the sultan’s wife is even mentioned, much less said to have put together the party.

Lady Fatima was an active patron of the arts, helping fuel the renewed flourishing of material arts under Qaytbay. It’s generally rare to find artifacts dedicated to women, but in the case of Lady Fatima a number of pieces have survived that were commissioned by her and engraved with dedications to her.

Among them is a brass ewer dedicated to her, owned by the Victoria & Albert Museum. As the museum points out, it’s unusually decorated, with luxuriant trees filled with birds and bands of animals, including elephants, antelopes and lions. Also picured here are a brass basin and candlestick that Lady Fatima commissioned. When the Flemish nobleman Joost van Ghistele visited Cairo in the early 1480s. he reported meeting a European goldsmith named Francisco Tudesco who was close not only to Sultan Qaytbay but also to his wife Fatima.

Qaytbay finally got his male heir in 1482 when his concubine Asalbay, an enslaved Circassian, gave birth to a son, Mohammed, who would eventually succeed his father as sultan.

Still, Lady Fatima’s status in the court and harem was undiminished. Bolstering her position, Khas Bak women were married to several of the top emirs in Qaytbay’s court.

One of her cousins, a granddaughter of Lady Zaynab, was the wife of the most senior man in Qaytbay’s regime, his grand chancellor Yashbak min Mahdi. Fatima’s sister, Aysha, was first married to Qaytbay’s nephew, Janam, a promising and handsome young man whom the sultan appeared to be grooming for great things. They had one of the most glorious weddings of the era. Yashbak min Mahdi himself led the groom’s horse in the wedding procession through Cairo’s streets, decorated in streamers and lit up with lanterns. Not long after, however, Janam fell ill and died, only in his 20s, just after paying a visit to Yashbak’s home —fueling rumors that Yashbak had poisoned him to rid himself of a potential rival.

But Aysha gained an even more powerful husband a few years later when, she married another nephew of Qaytbay, Emir Aqbirdi. He had just been appointed grand chancellor to replace Yashbak, who had been killed in battle. Aqbirdi became the sultan’s right-hand man, not only the most important military commander but also the top overseer of much of the sultan’s finances. So the two sisters were wives to the two most powerful men of the sultanate.

Throughout this time, Lady Fatima was buying up properties.

She was a sophisticated investor who amassed an estate rivalling those of the most prominent men of her time, says Carl Petry, the great modern scholar of the Mamluk era. According to his examination of Fatima’s purchases (7), she bought at least 11 pieces of agricultural land in the Delta and Upper Egypt and more than 100 properties in and around Cairo, including shops, housing units, reception halls, storehouses, gardens and caravanserais, a couple of stables and a waterwheel. All of it produced a regular income from rents.

She parked all this real estate under the protection of a Waqf.

Women were significant users of waqfs throughout the Mamluk era. They often created waqfs from of their own personal property. Also, men regularly named their wives and daughters as beneficiaries, guaranteeing them an income, or supervisors of their waqfs, giving them authority.

Under the Mamluks’ system of a constantly renewing elite, the sons of emirs usually disappeared into irrelevancy, unable to inherit their fathers’ political position. Daughters, however, could marry other emirs, keeping them in the upper echelons of power where large fortunes could be amassed. As a result, women were an important preserver and generator of cross-generational family wealth.

The Khas Baks illustrate this perfectly. Remember, they were originally not a particularly monied family. It was only with Lady Zaynab that they became known for their riches.

Zaynab likely started building her fortune as her husband rose through the Mamluk ranks. Once Inal became sultan, she raked it in.

Petitioners who sought positions didn’t just give money to the sultan: Zaynab took a significant share in every gift and bribe, the historian ibn Taghribirdi writes. For example, when the sherif of Mecca died, his son gave Sultan Inal 50,000 dinars to ensure he inherited the post – and he gave Zaynab 5,000. There’s no sign anyone ever before had felt the need to bribe a sultan’s wife before this, and with so many positions to hand out, it would have meant a very large income for Zaynab.

No doubt, she put much of the money into properties and set up waqfs of her own. Also, her husband named her and their children as beneficiaries of one large waqf. On top of that, he created an even bigger waqf that brought in tens of thousands of dinars a year to pay for his large funeral complex in Cairo’s Northern Cemetery. After his death, Zaynab became that waqf’s supervisor with complete say over how its money was used.

WHAT IS A WAQF?

Waqfs are Islamic endowments, but they were also a vital financial instrument. Under a Waqf, you dedicate the income from a piece of land or real estate to a particular charity. That charity could be, for example, paying the salaries of mosque attendants in Mecca. Or it could be covering the expenses for a massive institution that you have built, like a mosque, a madrasa, a school for orphans or your own mausoleum.

The loophole is: The income from the properties under the Waqf often vastly exceeded the actual expenses of the charity. The surplus can go to various beneficiaries like your relatives and to the supervisor of the Waqf, who can be yourself or one of your relatives.

What a Waqf gives you is protection. Because a Waqf is sacred, the lands under it (in theory at least) can never be taken away, which was a big concern at the time because sultans, grasping for any income, frequently confiscated properties. With a Waqf, you also guarantee an income for yourself and your family and leave an inheritance for your children without dividing the property up among them. Throughout the 1400s, waqfs became more and more important, and by the end of the century, it’s estimated nearly half Egypt’s cultivatable land was under waqfs. (8)

For generations after Zaynab, Khas Bak women would be noted for their fortunes.

For Lady Fatima, her wealth and status gave her an important position in the bloody struggle for power that ensued after her husband Qaytbay’s death in 1496.

LADY FATIMA vs LADY ASALBAY

With Qaytbay gone, a new Great Lady replaced Lady Fatima in the Hall of Pillars: the concubine Asalbay, mother of the new sultan, 14-year-old Mohammed bin Qaytbay. Now in her 50s, Fatima had to leave the Citadel, her home for more than half her life, and move into her mansion here.

The next five years were stormy ones, with a succession of four sultans, each meeting a bloody end. Each sultan was linked to either Fatima or Asalbay, pitting the two women as active players on opposite sides of the murderous fight for the throne.

Fatima seems to have quickly started maneuvering to regain her place in the Citadel.

Rumors spread that she secretly married Emir Qansouh Khumsumiya, or Qansouh 500. If she did, it was a true power match. Qansouh 500 had been a senior emir under her late husband and was now the real ruler behind the boy-sultan on the throne. Popular, bold and boundless in his ambition, he seemed destined to become sultan himself. By marrying Fatima, he gained a wealthy backer who could win him support among Qaytbay’s former Mamluk soldiers. Fatima gained a potential avenue back into power and protection for her wealth. (The only drawback: The marriage might have made things awkward with her sister. Aysha’s husband Emir Aqbirdi was a biiter enemy of Qansouh 500.)

Not long after Qaytbay died, Qansouh 500 rebelled against Sultan Mohammed. Enjoying overwhelming support from the other emirs, he seemed poised to waltz into the Citadel and take the throne. But he underestimated his opponents, who launched a powerful counterattack. Wounded in battle, Qansouh fled Egypt. Outside Gaza, he was again defeated in battle and killed.

It’s said the man who beheaded him was none other than Fatima’s brother-in-law, Aqbirdi.

Almost immediately, Emir Aqbirdi took his own turn at trying to seize the throne. He raised a siege of the Citadel that dragged on for an entire month. But he too was defeated and fled to Syria. There, after eluding the sultan’s troops for two years, he died of illness. (Another Khas Bak woman, Lady Zaynab’s granddaughter Sitt al-Mulouk also lost her husband because of his support of Aqbirdi’s revolt. After the revolt’s defeat, her husband Emir Tani Bak Qara was exiled to Jerusalem. Soon after, the sultan ordered him strangled, right in front of his wife and children.)

Inside the Citadel, Asalbay had her own troubles to deal with.

You would think she was in a prime position. She clearly had significant authority over her son Sultan Mohammed. (The viceroy of Syria grumbled that he had to answer to a “boy and a woman.”) Also, her brother, Qansouh al-Ashrafi, was now the most powerful figure in the regime behind the young sultan, having proved his strength by organizing the successful defense of the Citadel during the two revolts.

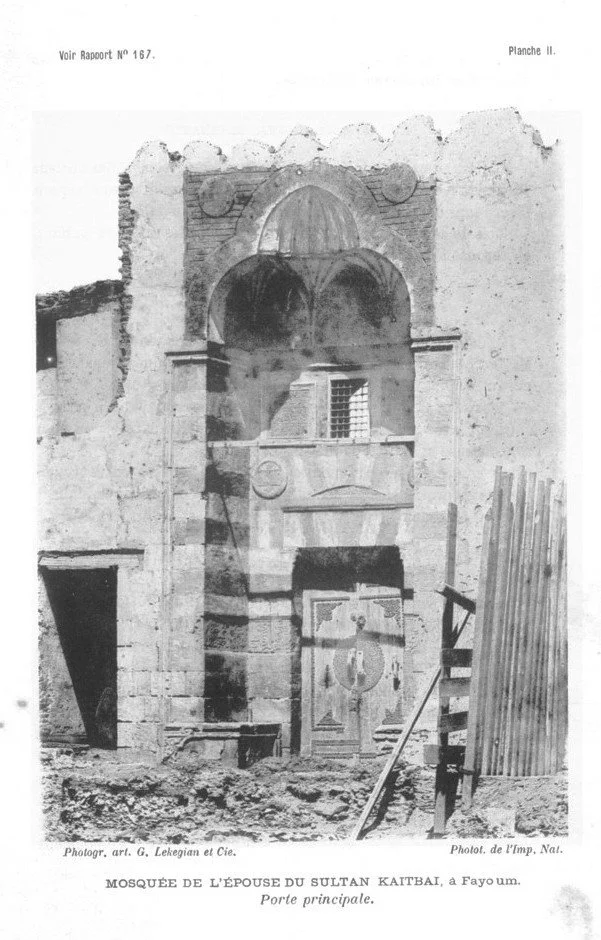

During her son’s rule, Asalbay built a mosque in Fayyoum and a bridge over the Bahr Yusuf canal, fulfilling a vow made to Sheikh Abdel-Qader al-Dashtouti, the most famed Sufi saint of the time, revered by Sultan Qaytbay. The mosque still stands today. These are an 1887 photo of the mosque and the bridge, and a 1895 photo of the mosque’s portal by the Comite (incorrectly referring to Asalbay as Qaytbay’s wife.)

But Asalbay had to wrestle with the difficult task of keeping a handle on her son. Sultan Mohammed turned out to be a rather Caligulan teen, notorious for debauched parties and rapes of women during his romps in the countryside. The senior emirs despised him. At the same time, she had to defuse the rising tensions between her son and her brother. It got to the point that she corralled them into the same room and made them swear on a Quran to remain loyal to each other.

The oath did no good. A group of emirs were conspiring to assassinate the sultan, and Qansouh secretly gave them his backing. Their plot unfurled in Giza, where Mohammed was partying with his friends. The conspiracy’s leader, Emir Toumanbay, lured him into an ambush and, with a single stroke of a sword from one of Toumanbay’s Mamluks, the teen was beheaded.

Asalbay’s brother Qansouh was elevated to sultan. He launched a persecution of the Khas Bak family to get his hands on their wealth. First, he arrested Fatima’s brother, Mohammed, and had him beaten until he surrendered a large sum. Next was her sister Aysha, who was jailed in the Citadel tower and forced up hand over 10,000 dinars. Then he imprisoned Fatima herself, and she had to sell some of her possessions to raise cash to give him.

Meanwhile, Asalbay clearly felt she couldn’t rely on her brother as an ally after he helped murder her son. She gave herself her own base of power by marrying Emir Janbalat, the man her brother had just named head of the military. In a show of the wealth Asalbay had accumulated during her years as concubine to one sultan and mother to another, it took 400 donkeys and 200 mules all day to carry her possessions out of the Citadel across Cairo to her new husband’s home in Azbakiyya.

She shouldn’t have bothered moving. In fact, Cairo’s porters would enjoy a boom in business as Grand Ladies moved in and out of the Citadel in rapid succession.

Asalbay’s husband Janbalat and Emir Toumanbay joined forces in a revolt, and after a quick assault on the Citadel, Qansouh was deposed and sent off to prison in Alexandria. Janbalat was installed as the new sultan, and Asalbay marched back into the Citadel in triumph in a grand procession through Cairo, escorted by hundreds of emirs, court officials and wives of the elite.

Less than seven months later, Emir Toumanbay raised yet another revolt, this time to take the throne for himself. After another brief Citadel siege, he ousted Janbalat, imprisoned him and had him strangled.

Now sultan, the first thing Toumanbay did was imprison Asalbay and force her to hand over 50,000 dinars. The second thing he did was strangle his top lieutenant who had helped him come to power.

The third thing he did: He married Fatima bint Khas Bak.

After five years in the cold, Fatima was once again the Great Lady of the Hall of Pillars. She moved from her mansion here back to the Citadel in a parade that the chronicler ibn Iyas assures us was even grander than that of Asalbay. Ibn Iyas recited to her a long poem that he wrote for the occasion, comparing her to the Caesars of Rome and the Shah of Persia and concluding, “May God protect her from the envious and extend her days in peace.”

Naturally, that didn’t work out.

Toumanbay’s time on the throne was even shorter than his predecessors’. By marrying Fatima, he may have hoped to boost his legitimacy with a link to Qaytbay and the Khas Bak family. But his vicious persecution of anyone he saw as a rival prompted the other leading emirs to rise up against him. Within 100 days, he was ousted and beheaded. Fatima retreated once more to her mansion here.

The man who rose to the throne, Qansouh al-Ghouri, would be the last Mamluk sultan to reign for any significant amount of time, about 16 years. Inheriting a treasury emptied by years of turmoil, al-Ghouri was voracious in confiscating the riches of the elite of the time. He imprisoned Asalbay to wrest funds from her, then exiled her to Mecca, where she died in 1509.

But in a sign of respect, al-Ghouri left Lady Fatima in peace for what was left of her days.

She lived for about three more years, and when she passed away in 1504, she was granted a grand funeral procession through the streets of Cairo. Only after she was buried did Sultan al-Ghouri force her brother and sister to hand over to him the entirety of Fatima’s huge collection of properties.

THE LAST KHAS BAKS

Those years of turmoil left most of the Khas Bak women widowed or abandoned by the time Sultan Qansouh al-Ghouri ascended the throne in 1501.

But remarkably, one more generation kept the family in the halls of power.

The daughter of Lady Fatima’s sister Aysha, identified only as Bint Aqbirdi (who would be great-grandniece of Lady Zaynab) married Sultan al-Ghouri’s grand chancellor, Emir Toumanbay (a different one) in 1506.

Toumanbay was the most powerful man under al-Ghouri, and Cairo shook with the celebrations as the wedding procession wound through the streets, the chroniclers say. It’s worth noting that, according to the chroniclers, her father Aqbirdi was enormously wealthy, so both Bint Aqbirdi and her mother would likely have had considerable inheritances from him, along with their own family fortune. For the next decade, mother and daughter enjoyed a life among the top noblewomen in the court.

Disaster then struck when Sultan al-Ghouri was killed in battle against the Ottomans in Syria in 1516.

Bint Aqbirdi’s husband was quickly elevated to become Sultan Toumanbay II on Oct. 17, 1516. A few weeks later, Bint Aqbirdi moved into the Citadel. Like her aunt and great-grand-aunt before her, she arrived in a grand procession, carried in a decorated litter surrounded by senior officials and the wives of all the emirs. The sultan’s emblems of a silk umbrella topped by a golden bird were held over her head as she entered the Hall of Pillars to take her place as the Grand Lady.

It was the Mamluks’ final show of pomp and pageantry.

Destruction raced toward them in the form of the Ottoman Sultan Selim and his armies, marching from Syria toward Cairo. When they arrived, the bloodshed was horrific. In January, Sultan Toumanbay attempted a final stand on Cairo’s Saliba Street but was overwhelmed and fled across the river to Giza.

Ottoman troops rampaged through the city. They looted homes and hunted down panicked Mamluk soldiers and emirs hiding in mosques, shrines and graveyards, beheading on the spot whomever they found. Thousands were killed, and the streets of Cairo were strewn with headless bodies.

The palace of the Caliph, the religious figurehead of the Islamic world, became a place of refuge, crammed with dozens of the family members of the Mamluk elite. Among those who hid there from the horrors outside were Bint Aqbirdi and her mother. Also with them were two other Khas Baks: Her uncle, Lady Fatima’s brother Mohammed, who was married to one of the caliph’s daughters, and Lady Zaynab’s grandson, Ali, the last surviving son of Sultan al-Muayyad Ahmed (and so, let’s see… the second cousin once removed of Bint Aqbirdi.)

Toumanbay was finally captured and executed in April 1517. After more than 250 years, the Mamluk Sultanate was over.

Mohammed and Ali, the two most prominent surviving Khas Bak men, were shipped off to live in exile in Istanbul along with the Caliph al-Mutawakkil and other male children of senior Mamluks.

The last of the Khas Bak women, however, stayed in Cairo and retained their wealth into the early years of Ottoman rule. Naturally, Ottoman officials preyed on them for their money.

Bint Aqbirdi was targeted after one of her enslaved dancing girls fled to an Ottoman official and told him where her mistress hid her money. The Ottomans broke into the trove and took everything – furniture, jewelry, pearls, gold belts and luxurious fabrics. That wasn’t enough for them, and they forced Bint Aqbirdi and her mother to each surrender another 20,000 dinars.

And that is the last we hear of them. We don’t know how long Bint Aqbirdi or her mother Aysha lived after that. We don’t know the eventual fate of their relatives shipped off to Istanbul. We know that one of Lady Zaynab’s great-granddaughters, Farah, lived another few years, a quiet life of luxury and piety, reciting the Quran and giving charity to widows and orphans. She died in 1521 and left behind “considerable possessions,” we are told.

With that, the Khas Bak family fades from the records of history.

(1) Secondary sources sometimes identify Zaynab and Fatima as aunt and niece or even sisters. The original Mamluk sources are clear, Fatima is the grand-daughter of Zaynab’s brother, Khalil.

Waqf documents give Fatima’s lineage as ibnat al-Alay Ali bin Khalil bin Khas Bak. Al-Sakhawi says her father Ali was the son of Zaynab’s brother Khalil (DL 11:245). The scholar al-Biqai confirms this separately, mentioning “the son of her (Zaynab’s) brother, Ali bin Khalil bin Khasbak.” (Izhar al-Asr 2:258.) Al-Biqai is writing when Fatima was a child, well before she came to prominence, so he has no reason to mention her.

(2) Location of the palace is based on the description by Mohammed al-Sishtawi in “Muntazahat al-Qahira fi al-Asrayn al-Mamluki wa al-Uthmani,” p 130. He cites accounts by al-Jabarti and Ali Mubarak’s al-Khitat al-Tawfiqiya.

(3) This area has undergone considerable change over the past two centuries. This first map shows the layout how it would have looked during the Mamluk Era (using the 1809 Description de l’Egypte map), with the approximate location of Fatima al-Khasbakiyya’s palace in red.

In the 1800’s part of this immediate area was cleared away for gardens and the palace of Mustafa Fadel, a younger half-brother of Khedive Ismail. That palace was later used by Ali Pasha Mubarak to house Egypt’s first official archives, the Kitabkhana, as part of the era’s overhaul of the education system.

In the 1860s, Egypt’s first modern high school, al-Madrasa al-Taghiziyya — established in 1836 — was moved from its location in Abbasiyya to here and renamed al-Madrasa al-Khediviya. Its location was south of what would become Ahmed Omar Street. In 1950, it was moved to its current location, about a block north.

A 1915 map of the area, with the approximate site of Fatima’s palace marked in red.

(4) The original Emir Khas Bak was a great beauty, according to the chronicler al-Safadi, who was his contemporary. Handsome and tall, he was slender as a lance. His hair, running long down to his waist, could drive its beholder into a mad passion so powerful that no feeling of shame could contain it.

He was a mamluk of the great Sultan al-Nasir Mohammed bin Qalawoun, bought when the sultan was still a child. When the teenaged al-Nasir Mohammed was briefly ousted and sent into exile in the desert fortress of Karak, Khas Bak went with him. This built a bond between them, and when al-Nasir Mohammed was restored to power, Khas Bak remained a close companions.

Among modern scholars, there is some dispute over whether this was the Khas Bak from whom the family descended.

One reason is that al-Safadi actually gives his name as Emir Khas Turk in his biographical collection A’yan al-Asr (2:305:261). It’s the historian ibn Taghribirdi, writing a century later, who calls him Khas Bak al-Nasiri and adds, “I think he is the father of famed Bani Khas Bak group, but God only knows” in his bio in al-Manhal al-Safi (5:197).

For what it’s worth, I believe this is the right Khas Bak.

Regarding the discrepancy, the name “bin Khas Bak al-Turki” appears in the names of later members of the family. So it’s possible the name shifted, keeping the Turk element in a new form. For example, ibn Hajar refers to Lady Zaynab’s grandfather as “Badreddin Mohammed bin Khas Bak al-Turki” (Inba al-Ghumr 2:475 and Dhil al-Durrar al-Kamina 211). Ibn Iyas refers to Lady Fatima’s father as “Ali bin Khalil bin Hassan Khas Bak al-Turki” (BZ 3:302.)

Other objections center on confusion over Khas Bak’s son and birth and death dates that don’t match up. This is likely rooted in a mistake by ibn Taghribirdi, who incorrectly identifies this emir’s son as Gharseddin Khalil, an emir who was born in 813, well after Emir Khas Bak’s death.

Al-Safadi correctly identifies the emir’s son as a different Khalil — Salaheddin Khalil, who died sometime after 764/1362 (al-Wafi bil-Wafayat 13:248).

That date would allow for this Khalil to be the father of al-Badr Mohammed, Zaynab’s grandfather. But it’s perhaps more likely there were more, unmentioned generations between Emir Khas Bak and al-Badr Mohammed. Also, nothing requires Zaynab’s grandfather be from Khalil’s line, so he could descend from another, unnamed son of the original Khas Bak.

There is some positive evidence supporting this Emir Khas Turk/Bak as the family progenitor. Al-Sakhawi gives the biography (DL 5:62:227) of another member of the Khas Bak family — Abdullah ibn Mohammed ibn Lajeen ibn Abdel-Gamal ibn Nasireddin al-Nasiri. He says this Abdullah’s ancestor was a mamluk of al-Nasir Mohammed, which no doubt refers to al-Safadi’s Seifeddin Khas Turk/Bak.

(6) We learn of the daughter only because ibn Iyas reports her death and that of her mother on the same day in Rajab 897/May 1492 (BZ 3:288). Ibn Iyas says the daughter was young but ready for marriage, so probably in her mid-teens, putting her birth around 1478, before Asalbay gave birth to Mohammed bin Qaytbay.

(5) Al-Biqai says bint Jaribash’s palace was on the lake by the Mosque of Bashtak. My pet theory is that the Palace of bint Jaribash and the Palace of Fatima al-Khasbakiyya are in fact one and the same — that Lady Zaynab confiscated the mansion from her rival and then it made its way to her grand-niece Lady Fatima. This might be provable by looking at the Waqf documents of Lady Fatima, which survive.

(7) Carl F. Petry, “The Estate of al-Khuwand Fatima al-Khassbakiyya: Royal Spouse, Autonomous Investor.”

(8) Albrecht Fuess, “Waqfization in the Late Mamluk Empire.”